Unexpected Hyperelastic Swelling in Stiff Hydrogels: How Pushing on a Gel Pulls Water In

In every kitchen, you will find a familiar tool: the sponge. Best known for the humble task of cleaning ketchup from plates, it belongs to a class of materials known as porous structures, whose properties are far from ordinary. Porous structures can soak up and retain large amounts of fluid while still maintaining a solid framework—just think of how much water you can squeeze out of a sponge.

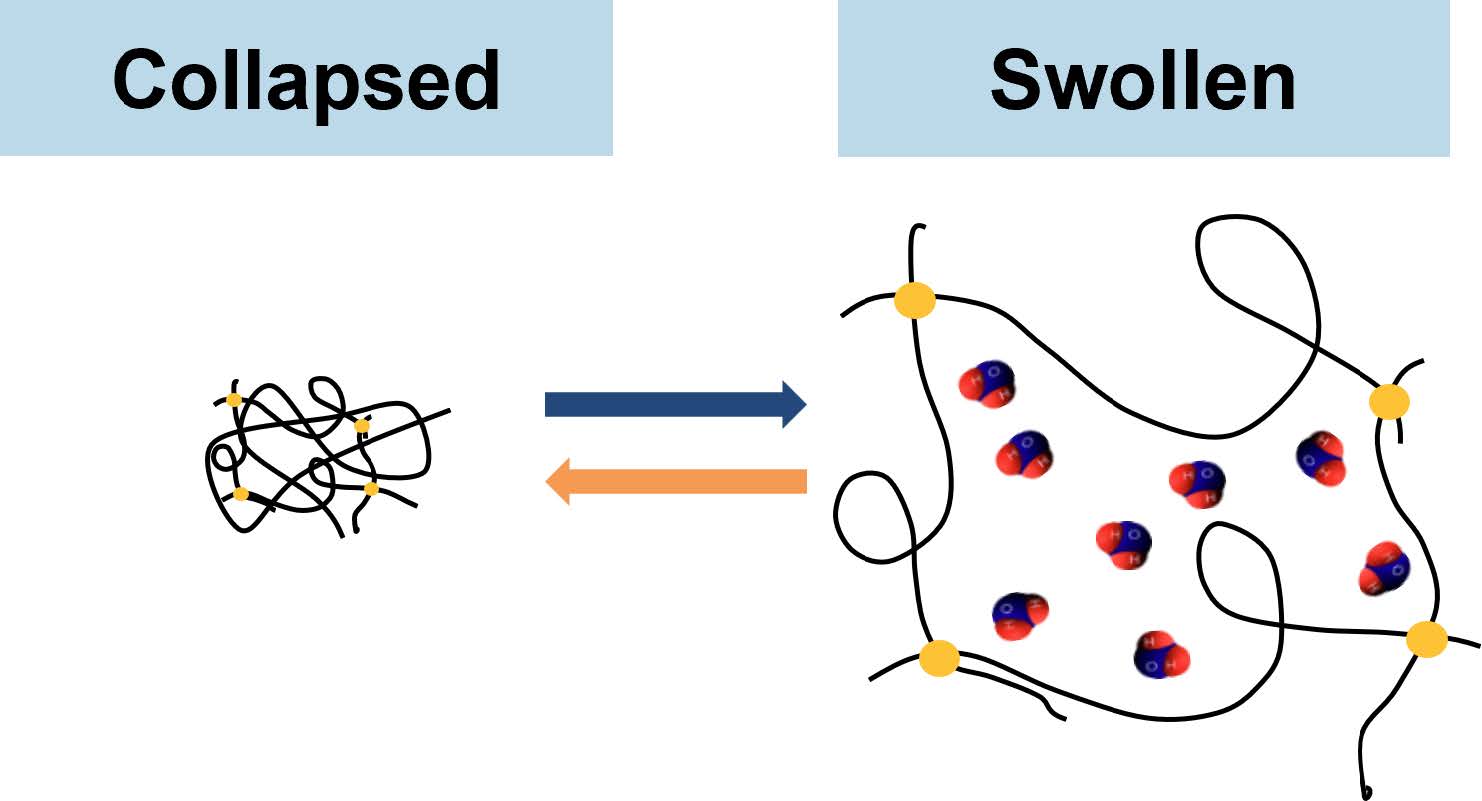

Typically, in the lab, scientists utilize hydrogels as a model system for porous materials. Hydrogels are polymeric networks swollen with water, in which the liquid is absorbed and integrated at the molecular level. You have probably interacted with hydrogels through contact lenses, colorful water-filled toys like Orbeez, or even in your own biological tissues.

Remarkably, some hydrogels contain as much as 99% water by weight, yet still hold together as solids. This unusual combination of softness and solidity gives rise to what scientists call hyperelastic behavior—the ability to stretch or swell far beyond what ordinary materials can sustain without breaking. A familiar object—the rubber band—is hyperelastic too, but hydrogels can deform in even more dramatic ways, swelling orders of magnitude in volume as they soak up water until reaching an equilibrium size.

Recently, however, researchers found a surprising twist: even when hydrogels are already swollen to near their maximum water content, they can expand further if you try to shear them. In a Physical Review Letters study, Wang and Burton of Emory University showed that when stiff hydrogels (with moduli of 10–100 kilopascals) are sheared or slid under load, they drew in additional water and swelled beyond their typical equilibrium volume. That result is deeply counterintuitive. When you squeeze a kitchen sponge, water is forced out. But under shear—rather than compression— Wang and Burton’s hydrogels do the opposite, pulling water in and growing larger. Earlier studies had shown that softer, weakly cross-linked hydrogels and biopolymer networks typically contracted under shear, and theory even predicted that this behavior should be universal. The discovery that stiff gels do the reverse flips that understanding on its head.

To uncover this effect, Wang and Burton used two complementary experiments. In one, they placed stiff hydrogels under a constant load in a custom-built tribometer and slid them back and forth. Instead of expelling fluid under stress, the gels imbibed water and visibly swelled, with the effect lasting for hours. In another experiment, they sheared hydrogels in a rheometer and measured the normal force—the force pressing outward on the plates. Rather than decreasing, as theory would suggest, the normal force increased quadratically with shear strain and remained elevated as long as the shear was applied. When the sliding or shearing stopped, the gels slowly relaxed back, confirming that the swelling was directly tied to the applied stress.

These findings suggest that stiff hydrogels possess an inherent dilatant response—pulling in fluid when sheared—that had gone unrecognized. The result not only overturns earlierpredictions about how polymer networks should behave under stress, but also points to possible explanations for long-standing puzzles in biology.

Remarkably, cartilage, which is structurally similar to a stiff hydrogel, also shows signs of rehydration and rejuvenation under load. Wang and Burton’s work hints that hyperelastic swelling may play a key role in keeping such tissues healthy, cushioning joints through cycles of stress and recovery.

By showing that stiff hydrogels swell when pushed past their limits, this research reshapes our understanding of how porous, water-rich materials respond to stress. What began with the humble kitchen sponge has led to a counterintuitive discovery: sometimes, when you push on a squishy material, it doesn’t squeeze water out—it pulls water in.