Alex Picksley, Anthony Gonsalves, Carl Schroeder, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Introduction

Advanced accelerator concepts aim to reduce the size and cost of large accelerator facilities. One such advanced accelerator concept is laser-plasma acceleration. A laser-plasma accelerator (LPA) works by propagating an intense laser through a plasma, driving a plasma wave in its wake. Electrons co-propagating with the laser can be accelerated in this plasma wake. The accelerating gradients in the plasma structure are orders of magnitude higher than those in conventional RF accelerator technology, compactly generating short, high-energy electron bunches. Owing to these ultra-high gradients, the LPA is being researched as a potential technology for applications in future high-energy physics machines, as well as for secondary radiation and particle sources, including X-ray free-electron lasers, compact muon beams, and gamma-ray sources.

Previously, LPAs have demonstrated the ability to generate multi-GeV electron beam energies, but these beams require improvements in electron bunch quality and better control over the accelerated beam parameters for many applications. This past year, the BELLA (Berkeley Lab Laser Accelerator) Center team at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), in collaboration with the University of Maryland, achieved controlled injection and acceleration of electron beams to 9.2 GeV with charge extending beyond 10 GeV, in 30-cm-long laser-plasma accelerators, using 20 J of laser energy [1]. Electron beam energies at 10 GeV can potentially drive hard X-rays in a free-electron laser, and this energy reaches the single stage energy gain appropriate for a future linear collider based on plasma accelerator technology.

Dephasing and Diffraction

Several mechanisms can limit the energy gain in an LPA. One such limit is dephasing, where trapped electrons, traveling close to the speed of light c, gradually outrun the accelerating phase of the plasma wave, which travels at the laser’s group velocity in the plasma vg < c. As a result, the maximum energy gain is limited by the distance over which the electrons remain in phase with the accelerating field. Lowering the plasma density increases the laser’s group velocity, thereby reducing dephasing and enabling higher beam energies by extending the acceleration length.

However, extending the acceleration length introduces a second challenge: diffraction of the driving laser pulse. In vacuum, a laser beam naturally diverges due to diffraction; in plasma, this divergence can cause a rapid decrease in intensity, weakening the laser-driven plasma wakefield and preventing energy gain. To mitigate this, a preformed plasma channel can be employed. These channels, which function as gradient-index fibers made from plasma, mitigate diffraction and can confine the high-intensity laser pulses over many Rayleigh lengths. They can be formed by creating a transverse plasma electron density profile that has an on-axis minimum (making the refractive index peak) and increases with increasing radius.

For optimal laser guiding, the transverse focusing effect of the channel must precisely balance the diffraction of the laser—a condition known as matched guiding. If a plasma channel is too “shallow” to match the laser spot-size, the laser spot-size and intensity oscillate along the accelerator, reducing the overall efficiency and degrading beam quality. In the worst cases, these oscillations make the plasma wave unsuitable for transporting and accelerating electron beams. Achieving this matching condition at plasma densities low enough to support a 10-GeV-class accelerator has previously been a challenge.

HOFI Plasma Channels

Recently, plasma channels formed by the hydrodynamic expansion of optical field ionized plasmas (HOFI plasma channels [2]) have received significant attention because they (a) can produce steep channels with matched spot-sizes less than 100 microns at the low plasma densities needed to achieve 10-GeV gain in a single plasma accelerator, and (b) are freestanding channels with no external structure, making them ideal for high repetition rate, long-term operation.

These channels are first formed by focusing a low-energy, femtosecond laser pulse using an axicon lens to generate an elongated, intense line focus that ionizes and heats a long cylinder of plasma. The plasma column expands radially, driving a cylindrical shock into the surrounding gas. The leading edge of the high-energy LPA drive laser pulses, which arrive a few nanoseconds later, will ionize any neutral atoms to form a steep plasma channel at low plasma density, ideal for a 10-GeV-class LPA. Figure 1 is a photograph of a 30-cm HOFI plasma channel formed in a hydrogen gas jet using a 40-fs laser pulse.

Figure 1: Plasma channel formed in a 30-cm hydrogen gas jet using the HOFI technique.

Matched Guiding

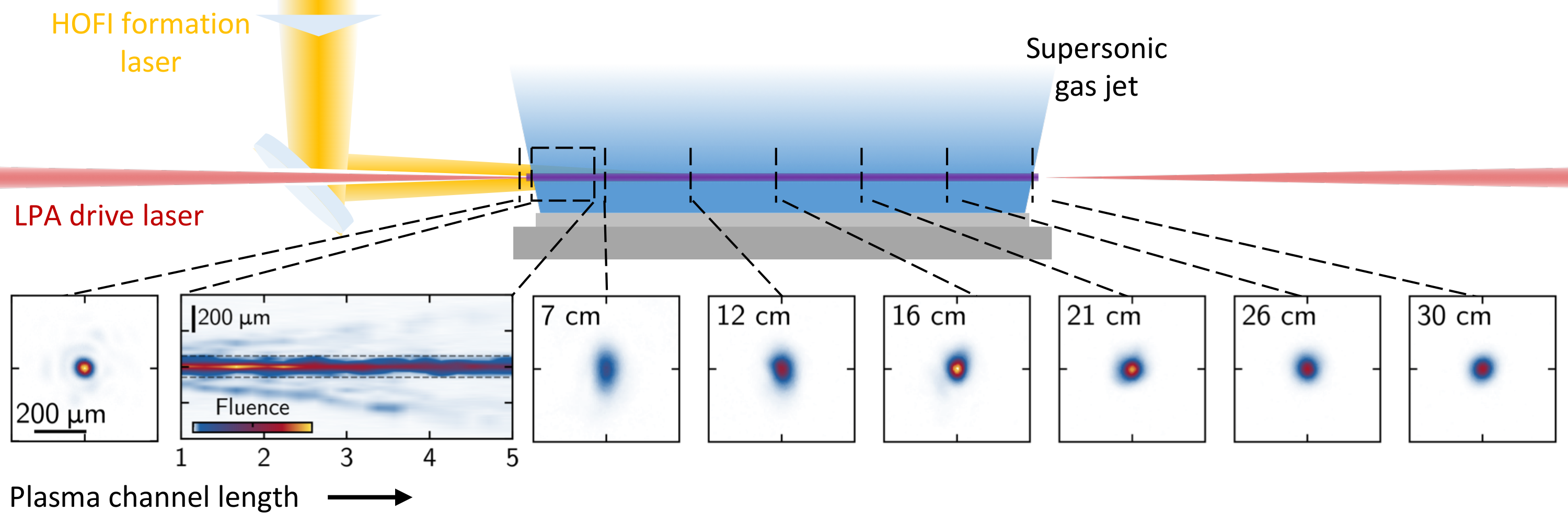

Measuring the laser and plasma dynamics within the plasma structure is often challenging. However, in this work, the team was able to see inside the accelerator itself through a novel diagnostic technique. By varying the length of the plasma channel shot by shot, the evolution of laser propagation and wakefield formation along the channel was directly observed, as shown in Fig. 2. Some of the key processes affecting electron acceleration were measured for the first time. In the initial 12 cm of propagation, energy coupling into higher-order transverse laser modes and leakage of that light outside the plasma fiber’s cladding were observed. Beyond this region, the drive laser transitioned into a quasi-stable, quasi-matched guiding regime.

Figure 2: Evolution of the drive laser in HOFI plasma channels with on-axis electron density of 1017 cm-3. Exit laser modes are shown for various channel lengths.

Electron Beams

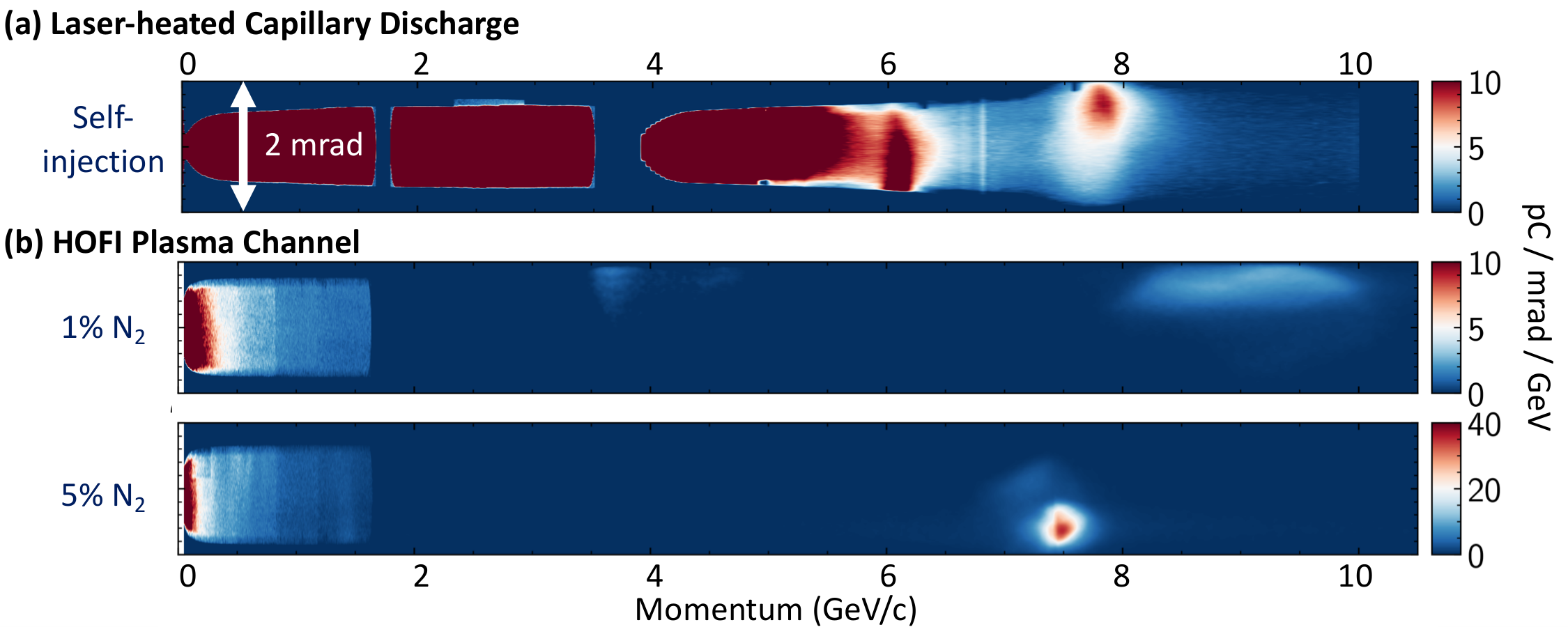

Electron beams were generated by introducing a 12-cm-long region of gas doped with nitrogen. Additional ionization of bound electrons in the nitrogen created an electron bunch that was subsequently accelerated to high energy over the 30-cm plasma channel. With this controlled, triggered injection, the quality of the laser-plasma-accelerated beam was greatly improved. Figure 3 shows the electron beam momentum distribution using (a) self-injection in a capillary discharge using 31 J of laser energy [3] and (b) local ionization-triggered injection in a HOFI plasma channel using 20 J of laser energy [1]. In our previous work [3], matched guiding was not possible at densities low enough to avoid unwanted ‘dark-current’ electrons being trapped throughout the accelerator length, which resulted in a continuous electron energy spread [as shown in Figure 3(a)]. In contrast, using HOFI plasma channels allowed us to achieve matched guiding at densities low enough to suppress dark current, thereby enabling improved beam quality.

By increasing the dopant concentration from 1% to 5%, the charge of the accelerated electron beam also increases. Additionally, the effect of beam-loading becomes evident—the amplitude of the accelerating field decreases as the bunch with larger charge absorbs more of the plasma wave energy. Here, beam-loading of the plasma wake reduces the energy gain from 9.2 GeV to 7.4 GeV.

Figure 3: Exemplary electron beams generated using the BELLA PW laser facility for (a) laser heated capillary discharge and 31 J laser energy [3], and (b) HOFI plasma channels and 20 J laser energy [1].

Next Steps

These results demonstrate that controllable, high-quality electron beams up to 10 GeV can be generated compactly. The BELLA Center is now working on improving the laser mode coupling into the plasma channel and implementing longitudinally tapered plasma channels, both to improve the efficiency of the accelerator. Ultimately, reaching higher energies requires staging many LPAs to further boost the energy for high-energy physics applications.

A compact source of electron beams accelerated to 10 GeV energy has many scientific applications, including as sources of radiation and secondary particles. Several research groups have demonstrated lasing of a free-electron laser using LPA electron beams [4], including recently at Berkeley Lab [5], and driving a free-electron laser in the hard X-ray regime using LPA electron beams is a goal of the international LPA community. Achieving this will require further improvement of the beam quality by controlling the electron beam injection process through laser-triggered injection. HOFI plasma channels are well-suited for developing laser-triggered injection techniques, opening the door to higher-quality LPA beams.

References

[1] A. Picksley et al., “Matched guiding and controlled injection in dark-current-free, 10-GeV-class, channel-guided laser-plasma accelerators,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 255001 (2024).

[2] R. J. Shalloo et al., “Hydrodynamic optical-field-ionized plasma channels,” Phys. Rev. E 97, 053203 (2018); A. Picksley et al., “Meter-scale conditioned hydrodynamic optical-field-ionized plasma channels,” Phys. Rev. E 102, 053201 (2020); B. Miao et al., “Optical guiding in meter-scale plasma waveguides,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 074801 (2020); L. Feder et al., “Self-waveguiding of relativistic laser pulses in neutral gas channel,” Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043173 (2020); K. Oubrerie et al., “Controlled acceleration of GeV electron beams in an all-optical plasma waveguide,” Light Sci. Appl. 11, 180 (2022).

[3] A. J. Gonsalves et al., “Petawatt laser guiding and electron beam acceleration to 8 GeV in a laser-heated capillary discharge waveguide,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 084801 (2019).

[4] W. Wang et al., “Free-electron lasing at 27 nanometres based on a laser wakefield accelerator” Nature 595, 516 (2021); M. Labat et al., “Seeded free-electron laser driven by a compact laser plasma accelerator,” Nature Photonics 17, 150 (2023).

[5] S. K. Barber et al., “Greater than 1000-fold gain in a free-electron laser driven by a laser plasma accelerator with high reliability,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 055001 (2025).