Claudio Emma, Nathan Majernik, Kelly Swanson, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

In 2024, researchers at the FACET-II National User Facility at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory achieved a milestone result in accelerator physics: the generation of the highest peak current, ultrashort electron beam ever produced. This achievement, recognized as addressing one of the U.S. Department of Energy’s “grand challenges” in particle accelerator science [https://science.osti.gov/hep/-/media/hep/pdf/2022/ABP_Roadmap_2023_final.pdf], opened new possibilities for research and exploration in high-energy physics, materials science, quantum electrodynamics, and beyond.

This result was the cumulation of several years of development in extreme beam shaping and involved the use of laser-based manipulation techniques, precise accelerator tuning, and indirect methods to diagnose beams so intense that traditional materials simply cannot withstand them.

The Motivation: Exploring Nature with More Powerful Probes

Particle beams are invaluable tools for probing matter, fields, and fundamental processes. The more spatially and temporally compressed the beam, that is “brighter”, the deeper we can peer into natural phenomena. The idea that more extreme beams can unlock new regimes of physics is not new, but the ability to generate and characterize them has been a subject of ongoing research.

In 2022, the DOE identified the generation of ultra-high-current, ultrashort electron bunches as one of four grand challenges in the field. FACET-II, a facility purpose-built to explore nonlinear and extreme regimes of beam physics, was the ideal platform for tackling this challenge. Our team recognized an opportunity to take a technique used in free electron lasers, namely laser-based energy modulation, and applied it in a new context: to create a uniquely powerful beam for experiments at the intensity frontier of beam-light and beam-matter interactions.

The Technique: Sculpting Beams with Lasers and Magnets

At the core of the approach is a technique that might sound counterintuitive: we intentionally distort the electron beam early in its journey in order to shape it into something much more powerful downstream.

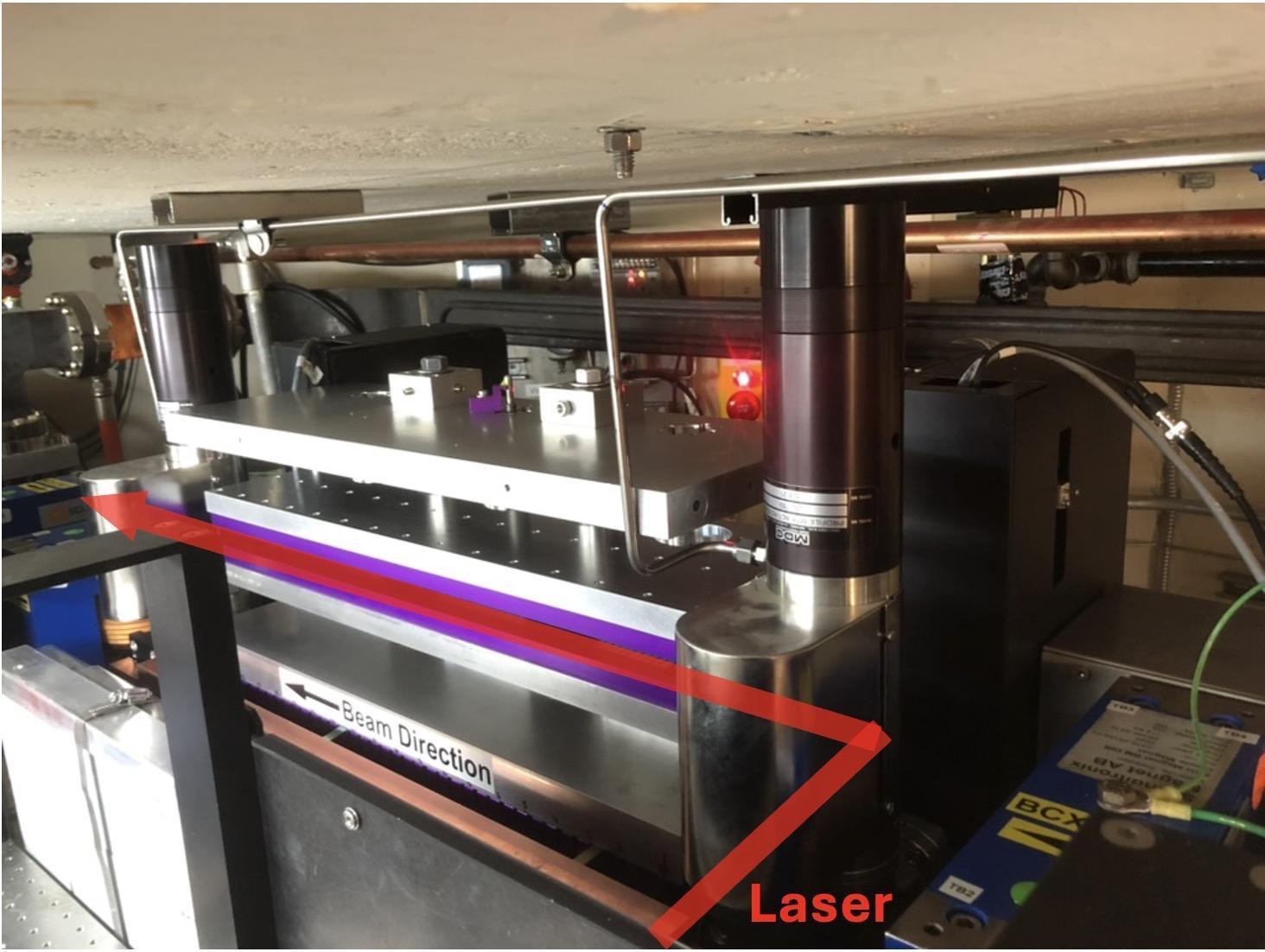

In the first 10 meters of the accelerator where the beam is still at relatively low energy, we co-propagate it with a laser beam through a device called a laser heater, which consists of an undulator—a magnetic structure that causes the electrons to wiggle side to side (see Fig. 1). If the wiggling frequency of the electrons matches the laser’s wavelength, the laser’s electromagnetic field can selectively add or subtract energy from different parts of the beam. By shaping the temporal profile of the laser, we can imprint a micron to millimeter-scale energy modulation onto the beam with high precision.

Figure 1: The laser heater undulator installed in the FACET-II beamline.

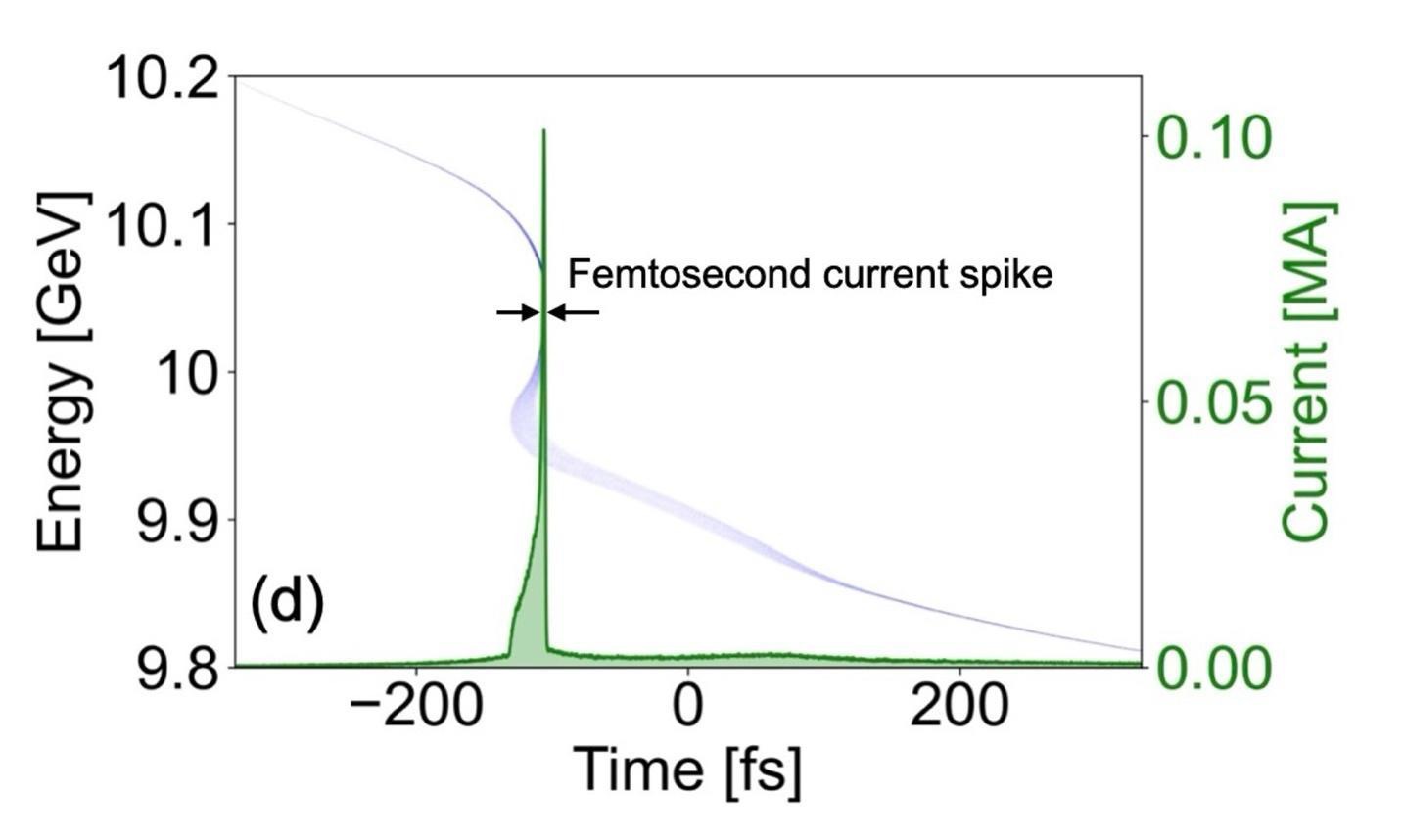

From there, the beam is accelerated to 10 GeV over a kilometer-long stretch of radiofrequency cavity linacs. These linac sections are interspersed with three magnetic bunch compressors. Throughout this process, collective effects act back on the beam, transforming the initial energy perturbation into an intense current spike. The result is an ultrarelativistic electron bunch just a few microns long, carrying peak currents in the range of hundreds of kiloamperes and a peak power of more than a petawatt (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Simulation of electron beam phase space after compression showing a femtosecond current spike with 10-GeV energy and 0.1 MA of peak current.

Challenges and Innovations

The interplay between laser modulation, acceleration, magnetic compression, and collective effects results in a vast parameter space. Much of our effort focused on developing strategies to identify beamline settings that would yield maximal compression while preserving beam quality.

A second major challenge lay in diagnostics. The peak fields of these ultrashort, high-current bunches are so strong that standard interceptive diagnostics (like scintillating screens) are unusable since the screens melt or vaporize upon interaction. Instead, we turned to indirect measurements, using plasma ionization, synchrotron radiation from the beam, and simulation cross-validation to reconstruct the beam’s time profile and peak current.

Another technical hurdle was controlling the laser shaping process itself. Our current method for spectro-temporal shaping is effectively artisanal, involving customized optical masks designed for specific laser profiles. While effective, this approach limits flexibility. We are now developing programmable shaping methods using digital micromirror devices to enable more rapid iteration and on-the-fly tuning of the laser profile.

Notable Insights and Implications

One of the most compelling aspects of this work is how it demonstrates the practical versatility of laser-based beam shaping at high energies. While the concept of shaping electron beams using a laser heater is well established, particularly in the context of free electron lasers,we’ve shown how it can be extended and optimized to produce extreme current profiles suitable for a broader range of applications. By tailoring the laser pulse shape, we can generate isolated current spikes or, in principle, construct a train of ultrashort electron bunches. This has implications for stroboscopic pump-probe experiments or plasma wakefield excitation with complex drive structures. Conversely, the same approach can be used to mitigate unwanted microbunching in the beam, helping to stabilize experiments that are sensitive to fine-scale structure.

This kind of tunability suggests the method is not only a way to generate record-breaking beams, but also a platform for a wide range of beam shaping applications. The ability to produce customized beam structures on demand could become an enabling technology for future user experiments.

Scientific Impact and Applications

We are already delivering these beams with high-current spikes to user experiments at FACET-II. One area of immediate impact is plasma wakefield acceleration. Because of the extreme current densities, these beams are highly effective at ionizing gases and driving large-amplitude plasma waves. This leads to more stable and efficient acceleration conditions and improved control over witness beam injection and energy spread.

But the applications extend well beyond accelerator R&D. If directed through an undulator, these beams could produce high-brightness, ultrashort x-ray pulses for studying atomic and molecular processes. They could also be used to probe quantum electrodynamics in strong-field regimes, including under conditions that are relevant to astrophysical environments. These capabilities position FACET-II as a uniquely capable facility at the intersection of accelerator physics, high-energy physics, ultrafast science, and strong field quantum physics.

Looking Ahead: Toward Megaampere Beams

While our current technique has pushed beams into the petawatt regime, we are already planning the next step forward. Our goal is to increase peak beam current by another order of magnitude and to reach the megaampere (MA) scale.

Achieving this will require extending the laser-based compression technique by employing plasma-based beam compression. This next-generation technique will take advantage of the enormous gradients in a plasma wakefield accelerator to modulate the electron beam for compression to the MA scale.

We are currently installing the hardware needed to test plasma-based compression at FACET-II, and expect early demonstration results in the near future. If successful, this could unlock a new capability for the facility: delivery of custom-tailored, megaampere-class beams on demand.

Conclusion

The generation of petawatt-class electron beams at FACET-II represents a major step forward in beam physics, opening new frontiers for accelerator-based science. This achievement reflects the effective integration of laser-based beam shaping, precise accelerator tuning, and advanced diagnostics, and highlights the kind of progress that can be made when established techniques are pushed to new regimes.

We are excited to continue refining these techniques, exploring their broader applications, and sharing the platform with users from across the physics community. Whether probing the boundaries of quantum theory, driving novel acceleration schemes, or simply exploring what’s physically possible, this work underscores a central tenet of our field: better beams lead to better science.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the team of scientists, engineers, and operators at FACET-II and SLAC, and support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics.