Stephen Milton, TAU Systems LLC

TAU Systems [1] was founded four years ago with the premise of bringing laser-powered accelerators to the commercial market. But why do we think this is a sensible idea? It pays to look at the history of linear accelerators first.

Just over 100 years ago the linear accelerator (linac) was first theorized by Gustav Ising (1924) and subsequently realized in the laboratory by Rolf Widerøe (1928). Key metrics for a linear accelerator are the gradient in MV/m and total accelerating energy achievable, typically in units of MeV for electrons. Another major step in the progress of linacs to achieve even higher beam energies was made by Luis Alvarez when he applied high-power, tuned rf amplifiers to drift-tube linac technology and reached a record proton energy of 31.5 MeV (1947). William Hanson, however, taking advantage of the electron reaching relativistic velocities at quite low beam energies, built the first traveling-wave electron accelerator at Stanford University (1947). By using disks to load a waveguide structure, he was able to adjust the phase velocity to match the electron’s velocity, essentially the speed of light, and therefore accelerate electrons over very long lengths and to very high beam energies. Since that time linacs, using very much the same basic technology, have progressed to higher and higher beam energies, with the highest energy achieved by the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center [2] (now SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory or simply SLAC) at 50 GeV. But achieving this high energy came at a price: the cost of real estate. The SLAC linac was 2 miles in length, a size that earned it the moniker “The Monster”.

But there are limits to the gradient one can achieve with a copper-based linac structure. Eventually the surface fields become so large that the copper ionizes, and an arc occurs that damages the copper and the resonant structure of the linac. While higher values are certainly possible, typical operational gradients tend to be in the range of 10s of MV/m.

In 1979 Tajima and Dawson [3] proposed another way to create high gradients. By passing a high-peak-power laser through a gas, a plasma is generated, and a plasma wave is formed that can generate gradients far above those in a typical linac. The brilliance here is that unlike copper, the “accelerating structure” is fully ionized. Indeed, the gradients that can be achieved in this plasma “wake field” can reach 100 GV/m—more than 1000 times that typically capable in a conventional linac. However, it took a couple of decades before such a laser-powered accelerator (LPA) showed clear signs of success.

For years, LPAs could generate high-energy electrons, but struggled with beam quality, particularly with large energy spreads that limited their usefulness. This changed with the discovery of the “bubble regime”, as described in the 2004 “Dream Beams” Nature papers [4-6], where a powerful laser is tightly focused into a low-density gas. Under proper conditions, and particularly when the gas density profile is suitably conditioned, a high-quality, low-energy-spread electron beam can be generated. These advances were made possible thanks to improvements in computer simulation algorithms, faster computers, and better laser technology, thus turning the idea of building sources of compact, high-energy, monoenergetic electron beams into reality.

Now many years on from that seminal paper beam energies above 10 GeV have been achieved [7-9], and there are signs of even more promising results on the near horizon. But just as important, our theoretical understanding of the LPA continues to mature, computer processing continues to grow exponentially, and the size and cost of suitable drive lasers continues to shrink while the repetition rates increase. One sees research papers now not simply focused on the LPA itself, but on its refinement and applications. Stable operations have been achieved over long periods of time [10, 11]. Use of these beams as a driver for a compact free-electron laser has been documented [12-14]. Novel configurations have been designed and constructed to use LPA systems for compact radiation effect testing [15]. LPA systems have even been proposed as a compact and energy-efficient replacement for high-energy injectors to light source facilities [16]. The LPA is no longer just a curiosity of the laboratory but now appears set to be the primary beam source for a variety of applications. This is not simply an evolutionary step from conventional accelerator technologies, it represents a revolutionary leap, and a paradigm shift in how one views the field moving forward.

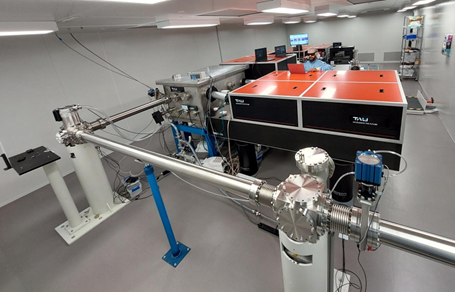

At TAU Systems we see a future for LPA-based systems and have positioned ourselves to capitalize off the tremendous progress made in the field over the last number of years. Such LPA-based systems will be clear winners over conventional systems for a multitude of applications requiring a cost effective, compact solution, particularly at beam energies above 1 GeV and repetition rates above 1 kHz. That combination, 1 GeV and 1 kHz, represents a clear turning point. The 1 GeV is readily achievable with an LPA using commercially available laser systems, and 1-kHz operation of an LPA has recently been demonstrated, albeit at significantly lower electron beam energies [17]. The current system at our Carlsbad, California facility, called TAU Labs, is designed initially for 100-Hz, 50-MeV operation, but is quickly upgradable to 200-300 MeV all while using a commercially provided laser system (Figs. 1-3). This LPA system in Carlsbad is designed to provide very small packets of high-energy electrons that will be used for radiation effects testing of electronics. However, this is but one application we are pursuing. Our team is also involved in developing other applications. For example, there is a huge need in electronics for compact, ultraprecise metrology systems, and in biology and the medical fields imaging is of essential importance. Properly configured, high-repetition rate, high-energy compact LPA-based systems can serve a role or possibly be the platform for completely new concepts.

TAU Systems also recognizes the key role of the high-repetition rate, ultra-short-pulse laser system as well as some of the unique requirements of the beam transport, diagnostics, and control systems that are needed to successfully build and operate an LPA-based system. The blending of the laser, plasma, and accelerator physics worlds with the commercial sector in the form of a first of its kind start-up has provided us with the opportunity to think in a vertically integrated fashion. We are constantly innovating to bring our concepts into reality at an affordable price point, but in a very agile fashion; we are quite proud of what we have accomplished to date.

As we look back over our past four years, it has been an exciting journey. There have been ups and downs, but the overall trend continues to be positive. More exciting, however, is looking into the future and watching our fledgling company grow by delivering this new and exciting tool, the laser-powered accelerator, to the world.

Figure 1: TAU's compact accelerator uses a 100-Hz laser system supplied by Thales. It is the first of its kind in the United States.

Figure 2: Our prototype LPA is designed to operate at 100 Hz to meet the requirements for commercial applications.

Figure 3: TAU Labs in Carlsbad, CA, will welcome a wide variety of commercial users, beginning with testing radiation effects in microelectronics.

References

[1] https://www.tausystems.com

[2] https://www6.slac.stanford.edu

[3] T. Tajima and J. M. Dawson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 43, 267–270 (1979).

[4] S. P. D. Mangles et al., Nature 431, 535–538 (2004).

[5] C. G. R. Geddes et al., Nature 431, 538–541 (2004).

[6] J. Faure et al., Nature 431, 541–544 (2004).

[7] C. Aniculaesei et al., Matter Radiat. Extremes 9, 014001 (2024).

[8] A. Picksley et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 255001 (2024).

[9] E. Rockafellow et al., NIM A 1077, 170586 (2025).

[10] A. Maier et al., Phys. Rev. X 10, 031039 (2020).

[11] F. Kohrell et al., Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams in review (2025).

[12] W. Wang et al., Nature 595, 516–520 (2021).

[13] M. Labat et al., Nature Photonics 17, 150–156 (2023)

[14] S. Barber et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 055001 (2025).

[15] G. Tzintzarov et al., IEEE Trans of Nucl Sci. accepted for publication (2025).

[16] S. Antipov et al., Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 24, 111301 (2021).

[17] L. Rovige et al., Phys. Plasmas 28, 033105 (2021).