Fusion Energy is Powerless

by Daniel L. Jassby (Retired from Princeton Plasma Physics Lab)dljenterp@aol.com

Status of Fusion-Derived Electricity

Fusion energy promoters claim that they will put fusion-derived electricity on the grid by the mid-2030’s. However, in 75 years of R&D no fusion device has ever produced one watt or one joule of electricity from the energy of fusion reactions, while the device subsystems consume megajoules of electricity during each operating pulse.

There are hundreds of fusion research devices worldwide, of which perhaps 10% can produce fusion reactions and 90% pretend that they could. While rabid promoters, hoodwinked government agencies, and the credulous news media gush over supposedly imminent fusion pilot plants, not one of the existing so-called reactors can generate an infinitesimal amount of gross electricity, while consuming multi-megawatts or megajoules. This situation was analyzed in a 2021 article in these pages [1], and nothing relevant has changed since then. (Here we define “gross electricity” as any electric output whatever, regardless of how much electric power is simultaneously consumed by the same device.)

Despite the grandiose promises made by fusion labs and private companies, even a modest demonstration of a few kilowatts of electric output while still consuming multi-megawatts is decades away. There are two basic reasons for these circumstances. The first is that attainable fusion neutron fluxes or fluences are simply too low, as covered in my 2021 analysis [1]. Today’s short-pulse facilities such as the NIF that can utilize the highly reactive deuterium-tritium fuel have minuscule duty factors, while long-pulse magnetic confinement systems have insignificant or even near-zero fusion burn rates. The second reason is that current fusion device concepts are simply not amenable to efficiently converting the products of fusion energy to electricity. Those products consist of energetic alphas that thermalize in the fusioning plasma and torrents of relativistic neutrons that leave it in all directions, including through every penetration in the reactor vessel.

Timeline for Electricity Demonstration

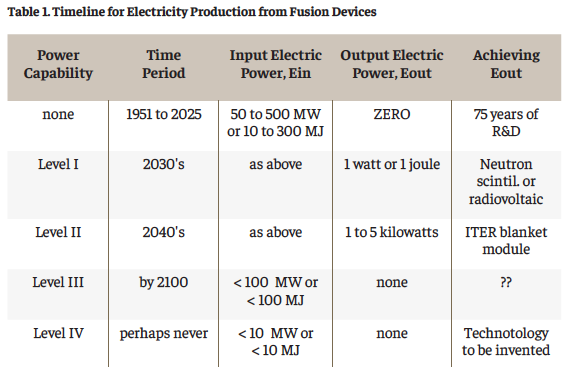

Table 1 indicates a realistic timeline on which various levels of fusion-derived electricity, Eout, might eventually be demonstrated. These demonstrations comprise 4 stages, denoted Levels I, II, III and IV in the following discussion.

Level I. It’s conceivable that within the next 10 years some fusion device using a gimmick or stunt may be able to produce a few fusion-derived watts or joules of electricity (gross, not net). Self-powered neutron detectors can produce only milliwatts. Watt-level output may be possible using neutron-induced scintillations, directly or indirectly, and in any case demands a more capable fusion device than anything operating today (2025).

Level II. For a more meaningful power demonstration, my 2021 article [1] outlined how a few kilowatts of electrical output could be generated with a single blanket module on the ITER facility, presently scheduled to operate with D-T in the 2040’s. This demonstration would be equivalent to the powering of a few lightbulbs by Idaho’s EBR-1 in 1951 [2] The output could be increased by recruiting more blanket modules, but would always be insignificant compared with ITER’s staggering 300 MW of electric power drain during a pulse.

In view of its turbulent history, there is substantial probability that ITER will never become operational with deuterium-tritium [3]; in that case even a kilowatt-level demonstration of fusion electricity will remain indefinitely far away.

Level III. The much greater challenge of producing net electric output from a fusion facility will be thwarted by the high power consumption of any fusion device and its support systems. That power drain combined with a structural inability to convert fusion product energy with high efficiency means that achieving net electric output (Eout = Ein) is likely impossible in the foreseeable future.

Level IV. Still more challenging, useful power generation (i.e., Eout :>> Ein) will not be attained until unknown and radical new technologies emerge for generating fusion reactions that do not require huge power consumption and are amenable to efficient energy conversion Such developments cannot presently be imagined and must await the next century or even later.

Terrestrial Fusion Power is Apparently Unreachable

Today there is no fusion device anywhere in the world that could perform even a Level I demonstration. Yet fusion promoters claim that they are building power reactors that will perform at Level IV as soon as commissioned in the next decade.

When will journalists, investors and planners recognize and concede that they have been mislead and manipulated by fusion promoters in national labs and private companies? They cannot and will not. This situation has persisted for 75 years and unlikely to change. Within a decade there may be some kind of setback to the present fusion frenzy when no visible results will have been produced. However, by then the promised schedules for power plants will have receded into the 2040’s (the standard decadal shift), and a new population of credulous investors and government planners will have appeared.

The following poem summarizes the status and prospects of fusion-generated electricity.

The Fusion Power Lament

by Daniel Jassby

They can’t produce one watt electric gross,

Fusion labs and firms are mainly comatose.

The longest crusade in technology's history

Is the hapless quest for fusion electricity.

Each plasma pulse consumes multi-megajoules

That cannot be reduced despite all plans to retool.

Yet producing just one kilojoule of electric gross

Is unlikely unless observers can self-hypnose.

Minuscule rep. rate plagues ICF

And paltry neutron fluence rules MCF.

Fusion energy flux lies beneath contempt

Confounding any power-making attempt.

My tiny solar-powered calculator

Can generate one full watt electrical,

Their billion-dollar fusion reactor

Has output purely hypothetical.

To generate even one watt electric net

Needs performance that will never be met.

No matter its cost in billions of quid

Their fusion device will only drain the grid.

Despite zero electric output a fusion pretender

Devours more power than an AI data center.

A voracious consumer of coolant resources,

Uses more water than a hundred golf courses.

Because vital tritium fuel does not exist,

Myths about “breeding” it still persist.

Low burnup of tritium is the greater threat

Incurring tritium losses that cannot be offset.

No laboratory fusion device has ever bred

Even one gram of tritium in a blanket of lithium.

They have to spend millions to buy it instead

And fuel self-sufficiency is purely delirium.

First there were only government labs,

Then universities jumped right in,

Now a hundred firms are prone to brag

They’ll become the fusion power kingpin.

Every player proclaims there is surely no crisis

Though all are afflicted with acute Theranosis.

Despite 75 years of hubris and bluster

Demand for billions more is all they can muster.

Planned projects are test reactors, pilot plants,

Demos and other fantasies,

Whatever can secure the grants,

But all are based on fallacies.

Take back your fancy roadmap

That says fusion power will come soon,

Your plans will once again be scrap

And fusion dreams once more will swoon.

No fusion lab or firm can produce electricity,

No fusion power for the rest of this century.

Perhaps they’ll have better luck in the next

If novel techniques can relieve fusion’s hex.

References

[1] Daniel Jassby, “Fusion Frenzy— A Recurring Pandemic,” APS Forum on Physics & Society, Vol. 50, No. 4, October 2021. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/APS/a05ec1cf-2e34-4fb3-816e-ea1497930d75/UploadedImages/P_S_OCT21.pdf

[2] Rick Michal, “Fifty years ago: Atomic reactor EBR-I produced first electricity,” ANS Nuclear News, Nov. 2001, p. 28.

[3] Daniel Clery, “Giant international fusion project is in big trouble,” Science, 3 July 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/giant-international-fusion-project-big-trouble.

Top